- Home

- W. c. Heinz

The Professional Page 22

The Professional Read online

Page 22

“I don’t know. It must have been midnight before I got to sleep. I didn’t feel like getting up this morning. How about you?”

“The same, except that I didn’t get up.”

“Eddie Brown!” Girot’s voice came up the stairs. “The telephone!”

“All right, Girot.”

“You can’t go down with that sweat on you. You’d better take that tea.”

“Find out who it is, will you?”

I walked to the top of the stairs.

“Girot? Find out who it is.”

“It’s the telephone operator. She said somebody wants Eddie.”

“Tell her to call back in a half hour.”

I walked back to the room.

“Maybe it’s Doc,” Eddie said.

“No. He wouldn’t call at this time. He knows you just came off the road.”

“This tea is almost too hot to drink.”

“You remind me of Tony Zale.”

“Why?”

“He was in Stillman’s one day, training for Graziano—just before they postponed that first fight. He’d finished his work and we were back in one of those little dressing rooms and Tony was sitting on a stool and Lester Bromberg was bending over him and interviewing him—you know the way Lester does. Art Winch came through the door, carrying a cup of hot tea for Tony in one hand. It was a warm day, and Art was stripped to his undershirt, and just as he went to hand the tea to Tony, Lester straightened up, and the cup and the tea went up into the air. It made a complete loop, and the tea spilled out and came down right inside the front of Winch’s undershirt, the slice of lemon and all.

“Well, Winch jumped about three feet off the floor. He ripped off the undershirt and the lemon fell to the floor and he’s jumping around there, screaming and grabbing a towel and Tony is sitting there, clapping his hands and laughing and shouting: ‘Stay in there, Art! Stay in there! You gotta be able to take it!’”

“Tony did?”

“That’s right. You know how quiet he was.”

“I know.”

“That’s why I remember it. It was the only time—in or out of the ring—that I ever saw him show any emotion.”

“So what happened?”

“Well, Winch is drying himself off—his chest was all red from the scalding—and Tony is still laughing, with his head back, and Winch says to him: ‘What’s the matter with you? You crazy? What’s so funny?’ And Tony said: ‘You. You’re always telling me how tough I gotta be. You’re always telling me that you gotta stay in there. So stay in there, Art. Stay in there yourself. You see?’”

“He made a lot of money, didn’t he, with Graziano and Cerdan?”

“Tony? He was a good fighter, and he had the right people around him—Pian and Winch and Ray Arcel.”

“He was plenty tough.”

“Winch was right. You’ve got to stay in there, otherwise find another business.”

“That’s right. You’d be surprised, though, at the number of fighters that aren’t that way at all. I mean, pretty good fighters. Anyway, people think they’re good. They don’t like it. I mean, how they got in the business I don’t know.”

“They have a manual dexterity—great reflexes, fast hands. They cover up.”

“That’s right, but that’s not enough. Not if you’re in there with a real good fighter. He’ll show you up.”

“Certainly. That’s the truth of it all. If it wasn’t so, boxing wouldn’t mean anything.”

“This other guy isn’t so tough. From the fights I’ve seen him in I know he’s not tough enough, and I’ll prove it.”

“Of course you will. You’ve got the equipment to do it.”

“I wish the fight was this Friday. I’m getting sick of it around here.”

“I know.”

It wasn’t a half hour. It was about twenty minutes after the first call that Girot shouted up the stairs again. Eddie had just come back from his shower and was finishing dressing, and I walked downstairs with him and stood talking with Girot while Eddie went into the booth.

“I need some change,” Eddie said, coming out of the booth. “It’s collect.”

Girot gave him some quarters, dimes and nickels, and Eddie was in the booth for five or six minutes.

“That was Ernie Gordon,” he said. “He wants to write something about Jay for today’s paper. Doc called him. I guess he called all the newspapermen.”

“That’s good.”

“He wanted me to say something about Jay. I didn’t know what to say.”

“I know.”

“I said he was with me for all those fights, and he was a great little guy, and I wish it didn’t happen. That sounds stupid.”

“What else could you say?”

“So you know what he asked me then?”

“What?”

“He said: ‘What does this mean to the fight?’ I said: ‘What do you mean?’ He said: ‘How do you feel about the fight now?’ I said: ‘I feel the same. I’m gonna lick the guy, only more so.’ What else could I say?”

“Nothing else. You did well.”

“Why does he call collect? He always calls collect.”

“He does it with all the fighters,” Girot said, shaking his head. “That’s no good.”

“He must make money, doesn’t he?”

“You know that, Eddie. You should know that.”

“I know what you mean. Plenty. So can’t he afford to pay for the call? I don’t care about the dollar-sixty, or whatever it is. Can’t he even pay that?”

“That isn’t all.”

“What isn’t?”

“When he writes his story he’ll dateline himself here in camp, and then he can collect expenses from his office.”

“Even when he is here he has no expenses,” Girot said.

“Is that right to do that?” Eddie said.

“He’s still a good reporter in that paper,” I said. “Why don’t we have our breakfast?”

After breakfast I walked with Eddie. When we got to the top of the driveway I suggested that we might walk south to the town.

“No,” he said. “It’s too flat. If I’m going to walk, the hills are better.”

“I just thought you might be bored with it. How many times do you see it, running it every morning and walking twice a day?”

“I don’t know. I’m not here to have fun.”

We walked to the top of the rise of the road north of the camp. I was trying to think of something to say to get Eddie out of it, and as we started down the gentle, curving-to-the-right slope of the other side, I looked at the vista, limited by the pines on the lake shore, half hiding the roofs of the summer homes and cottages and the lake itself, but open on the left, where two sloping fields lay bare in the sun. Once, long ago, they had been stripped of wood and growth and stone, and now they lay bare brown, waiting for a planting, probably in corn. To me they seemed to be breathing the warm spring sun the way a man breathes the air after a long try under water at the end of a long dive.

“Who do you think took Jay’s ring?” Eddie said.

It is inevitable. When a man has just died he is suddenly, for a time, more alive than he had ever been in his life.

“I don’t know,” I said.

“Doc thinks it might have been Penna.”

“I don’t think so.”

“I know. He told me. I don’t think so, either. Penna’s not a bad guy. Doc says you think it might have been Cardone or Boyd.”

“There’s no one else. I don’t necessarily think one of them took it. I’ve just eliminated the others.”

“How could anybody take a ring off somebody that just died?”

“I don’t know. During the war I passed up I don’t know how many rings and wrist watches and good German binoculars. I just couldn’t take them off the bodies, but some guys could. I might just as well have taken them. Somebody was going to.”

“I couldn’t have done it, either.”

“In the war,

at least, I didn’t resent the guys who did it. I rather admired that ability.”

“How do you mean?”

It was a chance to take his mind off Jay.

“They were realists,” I said, “and it was one of the things that made them good in combat. I never heard of a one of them having to go back to see the division psychiatrist because of what they called combat fatigue. That type won the war for us, and there’s really no basic difference between men in war and men in peace. When a thing is done it’s done. When a man dies he’s dead. If you can see things that way, and accept them, you’ve got life licked.”

“I still don’t see it.”

“You do in your own business.”

“How?”

“Take that dame who interviewed you the other day on television. To her it seems just as horrible for one man to punch another man into insensibility as it seems now, to you and me, for someone to strip a ring off Jay’s finger.”

“But that’s stealing.”

“I know, but that’s not what bothers us. If this ring or some money or a watch were stolen from Jay last week we wouldn’t be so aroused. We recognize that some people are crooks. What really gets us is that the ring was taken off the hand of a man who had just died. Am I right?”

“That’s right.”

“So, feeling as most people do about death, we can’t understand how anyone could do such a thing.”

“I sure can’t understand it.”

“And that television dame—that Bunny Williams—feeling as most people do about hurting other people physically, can’t understand how you can punch another man until you knock him out.”

“It’s not the same.”

“Of course not, because you have one attitude about the one, and another about the other. Suppose that television dame had given you a chance to explain what you feel about fighting another man, and hitting him. Suppose she had really been trying to find out the truth of you, and of fighting, instead of just trying to make her own point. If she had led you into expressing what you feel about hitting an opponent and knocking him out, what would you have said?”

“I don’t know.”

“All right, I’ll frame the question. You’re Eddie Brown—as Jimmy Cannon would say—and a week from Friday you’re going to fight for the middleweight championship of the world. To win this fight you’re going to have to hurt the other man more than he hurts you. Do you enjoy hurting other people?”

“No. I don’t think of it that way.”

“How do you think of it? What’s in your mind when you punch another man, as hard as you can?”

“I want to beat him. He’s trying to beat me, and I’m trying to beat him. That’s what it’s all about.”

“Is that all? Don’t you want to hurt him?”

“I don’t know. I don’t think of that. I think of beating him, like you do in anything else.”

“And when you knock him out, how do you feel? There he is, lying there. How do you feel?”

“I feel good, great. You try to get a knockout.”

“Ezzard Charles once told me that, after he had knocked a man out, he often started to think, that night or the next day, that maybe he could have won without knocking him out. He began to regret the knockout.”

“I don’t.”

“That was one of the flaws in Charles as a fighter. He wasn’t the complete fighter, and that showed in his fights and was one of the reasons why the people never rose to him. He could never understand that, and late in his career when he tried to turn slugger and go for the knockout he floundered because he was going against his true nature.”

“I know that. I could see it.”

“I don’t want to keep going back to Graziano and Zale, but if anyone saw their three fights he saw most of the truth of fighting. After the second one—the one that Rocky won—he was in the shower room in the basement of the Chicago Stadium. One eye was closed and there was a metal clip holding the cut over the other one, and the newspapermen were crowded around him asking him how he felt. He kept saying: ‘I wanted to kill him. I like him, but I wanted to kill him. I wanted to kill him.’ That was all he could say.”

“I know. I remember reading that. I was just a kid, starting to fight.”

“Did you believe that? Did you believe that he could like the other guy, and still want to kill him in there?”

“I don’t know if I believed it then. I believe it now. I’ve felt that way.”

“You have?”

“It’s just that you get so worked up in a fight. I mean, if it’s a tough fight, and the other guy is a good fighter and you’re both trying to take one another out. You like him for that, but the funny thing is it makes you want to kill him at the same time.”

“Rocky liked Tony and Tony liked Rocky. Each still thinks more of the other than he does of any other fighter. Three times they were ready to fight to the death, but do you know why they like one another?”

“Why?”

“Because of those fights. Each guy brought out the best in the other guy, and gave him his greatest fight and his greatest moment.”

“I go with that. I like the guys that gave me my good fights. I think of them a lot. I’d even like to see them again. I mean, someday just sit around and talk.”

“Marciano once told me the same thing.”

“He did?”

“He feels that way about Walcott, off their Philadelphia fight. He said: ‘It was my greatest fight, and I couldn’t have done it alone. I’ll always like Walcott for that.’”

“I feel the same way. I fought Al Morrow in St. Louis.”

“A real good fighter.”

“I’ll say. In the first round he hit me a punch under the heart I could feel in my legs. We fought that way for ten rounds. We never let up, and when I got the decision you know what I wanted to do?”

“No.”

“I wanted to kiss him. What would that look like?”

“I’ve seen fighters do it.”

“I mean, for ten rounds I wanted to kill him and he fought like he wanted to kill me, and then I wanted to kiss him. First I wanted to kill him. Explain that.”

“Suppose you had?”

“What?”

“Killed him.”

“I don’t know.”

“Don’t get me wrong. I understand this. I’m just trying to be an honest Bunny Williams, if there is such a thing, and bring out the truth in you. This is what she should have done on that show.”

“So why didn’t she? Why did she have to do it the way she did?”

“Because there isn’t enough truth in her to bring it out in someone else.”

“How come you like boxing so much?”

“Because I find so much in it.”

“How do you mean?”

“The basic law of man. The truth of life. It’s a fight, man against man, and if you’re going to defeat another man, defeat him completely. Don’t starve him to death, like they try to do in the fine, clean competitive world of commerce. Leave him lying there, senseless, on the floor.”

“I guess that’s it. I don’t know.”

“Look. I’m not supporting this. I’m not saying it’s good. I’m just saying it’s there. It’s in man, all men. I’m against violence. I hate arguments. I believe in a world where everything will be done through reason and with honesty and where force will be nothing. Centuries from now we may have this, but as of now there is still that remnant of the animal in man and the law of life is still in the law of the jungle—the survival of the fittest. As long as that’s true, I find man revealing himself more completely in fighting than in any other form of expressive endeavor. It’s the war all over again, and they license it and sell tickets to it and people go to see it because, without even realizing it, they see this truth in it.”

“I never thought of it like that.”

“I’ll go back to Zale and Graziano for one last time. I’ll go back to their first fight in the Yankee Stadium. It

was the best of the three.”

“It was?”

“I say it was, and it set the pace for the others. That same year the Dodgers and the Cardinals tied for the National League pennant, when the Dodgers blew their last game of the season. After the game we all went down to the clubhouse at Ebbets Field and the ballplayers were scowling and staring at their lockers.

“We went into Leo Durocher’s office. Now I’m for Durocher as a baseball manager. I think he represented, better than any other manager since John McGraw, the competitive essence of the game. Durocher was a symbol of what baseball—any game—is all about, the overwhelming desire to win, and as we walked in he was standing in the middle of his office, pulling on a pair of peach silk undershorts, and somebody said: ‘Well, Leo, what about it?’

“‘What about it?’ Leo said, straightening up and looking at us. ‘I’ll tell you what about it. We’ll play ’em till the snow flies.’ So there stood the baseball writers, writing this down, and, as I said, I’m not knocking baseball or Leo. This was a fine, fighting quote—for baseball—but as I walked away I was thinking of something else. You know what?”

“You said Zale and Graziano.”

“That’s right. Leo was going to play them till the snow flew, and one week before I’d seen Zale and Graziano, two men standing toe to toe under the lights in Yankee Stadium, literally trying to take one another apart with that mass of mankind sitting in the darkness around them and screaming for more. It was like two prehistoric monsters, knee deep in the primeval ooze, ready to fight to the death and with the jungle all around them echoing to the noise and the horror of it.”

“It was that good a fight?”

“Yes, and it was the truth. When you want to beat another man, you try to beat him, literally. You don’t try to hit behind the runner, or work the pitcher for a walk or break a curve over the corner of the plate. These are the refinements of civilization.”

“They’re two different things. A fighter is a fighter, and a ballplayer is a ballplayer.”

“No. A ballplayer is a fighter, too. What does the ballplayer do, when it comes down to essentials? When hitting behind the runner, or breaking off the curve isn’t enough? You’ve seen them do it. When it all becomes too much, they strip off their gloves and drop their bats and go at one another with their bare fists.”

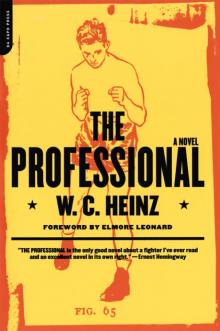

The Professional

The Professional