- Home

- W. c. Heinz

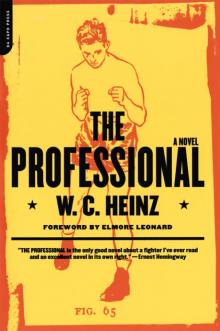

The Professional

The Professional Read online

The Professional

The

Professional

W. C. Heinz

Foreword by Elmore Leonard

DA CAPO PRESS

Copyright © 1958 by W. C. Heinz

Foreword copyright © 2001 by Elmore Leonard, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Design by Jane Raese

Set in 10.5 point ITC Century Book

Cataloging-in-Publication data for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

First Da Capo Press edition 2001

Reprinted by arrangement with the author

ISBN-13: 978-0-786-74842-6

Published by Da Capo Press

A Member of the Perseus Books Group

http://www.dacapopress.com

Da Capo Press books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the U.S. by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 11 Cambridge Center, Cambridge, MA 02142, or call (617) 252-5298 or (800) 255-1514, or e-mail [email protected].

To George Hicks

Also by W.C. Heinz

The Professional (1958)

The Fireside Book of Boxing (1961)

editor

The Surgeon (1963)

Run to Daylight! (1963)

with Vince Lombardi

MASH (1968)

with H. Richard Hornberger, MD

Emergency (1974)

Once They Heard Cheers (1979)

American Mirror (1982)

The Book of Boxing (1999)

coeditor with Nathan Ward

What a Time It Was (2001)

Contents

Foreword

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Foreword

Elmore Leonard

The way I remember it, I read The Professional when it came out in January 1958, and for the first and only time in my life wrote to the author to tell him how much I liked his book.

I must have taken months to work up the nerve, because the reply from Bill Heinz, which came within a few days, was dated October 11, 1958, my birthday. He wrote:

You are only the second person, outside my circle of friends and acquaintances, who has felt impelled to comment to me or the publisher about The Professional. The first was Ernest Hemingway, who cabled his compliments to Harper’s about six days after the book came out. You are a writer, however, and understand, as does, of course, Papa, and that is what gives your letter added importance to me.

In my letter I told Bill that I’d bought the book or got it from the library—I’m not sure now which it was—after reading a review in Time. In his letter, Bill said it must have been Newsweek, because “Time blasted it and me.”

But I’m positive it was the Time review and still recall it being extremely unkind to both the work and Bill’s style.

I got hold of the review again recently to see why it prompted me to read the book. It appeared in the magazine’s February 13, 1958, issue and it was brutal: an opinion laden with showoff references—the British critic Cyril Connolly, for God’s sake—the reviewer pontificating on his belief that sportswriters should stick to sportswriting and not “tangle with the elusive opponent, literature.” It was acceptable, though, to wax literary in writing the review, despairing that “you cannot write novels about boxers with boxing gloves.” Read that again. I think he meant wearing the gloves when writing, but who knows? It belongs in that filler The New Yorker used to run called “Block That Metaphor.”

Reading the review I must have been thinking, The man doesn’t get it. He admits the story is a wonderful example of tough prose, but still doesn’t get it. He says, “It’s about the fight game, see.” Which is what reviewers do, end sentences with the word “see” to indicate that anyone can write tough prose. All you do is imagine Cagney, or Edward G. Robinson, talking out the side of his mouth.

Since there was no byline, I asked Bill recently if he knew who wrote the review. He said “No, they used to shoot from the woods in those days.”

Perhaps the review irritated me to the point where I had to read the book. I did, I ate it up, and told Bill as well as I could why I liked it.

In his letter in ’58 he said,

It pleases me that you observed how I employed dialogue in character development. I have long felt that most writers get between the reader and the characters. Characters, to live, must be permitted to think for themselves, each with his own manner of speech and level of thought. The writer should be kept out of there. He should not tell, but show.

If I was praising his work for the right reasons, I must have been on the right track at an early stage of learning to write fiction, developing a style I might be able to handle. At least I knew the difference between showing and telling, allowing the characters and their voices to carry the story.

But it was Bill Heinz who brought it home in his letters, and showed exactly how to do it in his book.

He said in that first letter, “Also I’m happy that you admired the restraint. The best fighters I have known have all had that—the ability to keep the fight moving at their distance and always directly in front of them, pursuing their aim with a quiet purpose with all kinds of hell breaking loose on all sides from the throats of amateurs.”

Perhaps that will always be true, the showy writer, novelist, or critic, getting more attention than the pro.

Shortly after our exchange of those first letters, Bill arrived in Detroit to interview Gordie Howe, then the backbone of the Red Wings, for The Saturday Evening Post. Bill came to our home for dinner on a Sunday and missed his ride with Howe to Olympia, where the Wings played their games at that time. Howe lived only a few blocks from us, but I got Bill to his house a few minutes late. The outcome, we drove down to Olympia together, I got to meet the Wings and watch the hockey game from the press box. After he returned home to Connecticut, Bill sent a copy of The Professional inscribed to my wife and me: “Two fine people who, one Sunday in Lathrup Village, saved my life.”

But the highest point of Bill’s visit, for me, was spending a couple of evenings with him, listening to his stories about boxers and ballplayers and talking about writing and Ernest Hemingway.

He told me that he met Hemingway during the war in Germany, when he was covering the Allied advance for the New York Sun and Hemingway was sending his dispatches to Collier’s. Hemingway had taken over a house in the Hurtgen Forest that became a meeting place for the correspondents. Bill presented Hemingway with a bottle of Scotch in appreciation of the man’s work. Hemingway was so moved he urged Bill to use his bedroom, rather than sleep on a cot in the attic, for as long as Bill was there—an invitation to a stranger that Bill found touching but that he turned down.

It was Toots Shor, the New York restaurateur, who sent a copy of The

Professional to Hemingway in Cuba. Hemingway cabled the publisher his reaction to the book. Bill’s editor called to relay the quote, and as soon as they’d hung up Bill told his wife, Betty.

Quote: The Professional is the only good novel I’ve ever read about a fighter and an excellent first novel in its own right. Hemingway. Unquote.

“Well,” Betty said, “I think we should have a drink.”

They sat, late that afternoon, before the fire in the house in Connecticut, sipping their drinks, silent at first, and then she said, “You know, I remember when you were first starting to write your short stories. After working all day you’d come out looking depressed and you’d go over to the bookcase and take something of Hemingway’s down and read it. This must be the greatest day in your life.”

“If you don’t stop,” he said, “I’ll start to cry.”

“A tear,” she said, “just dropped in my drink.”

Bill wrote and thanked Hemingway, telling him what Betty had said and mentioned the panning he had taken from Time. Hemingway wrote back:

What I cabled was straight, and you believe it. Critics, mostly, don’t know much about it. They can’t tell the players without a scorecard.

It was Betty who had prompted Bill to write the book he had been thinking about for several years. He had sold a piece on Eddie Arcaro to Look magazine for a lot of money and Betty said, “Now you can afford to write your book, so write it.”

Nine months later The Professional went to Harper, and they grabbed it.

By the time I had turned to the second page of the book, I was aware of Hemingway’s influence. It was Bill’s use of the word and.

“She was sitting there with another woman, and they were in their late thirties and their coats and accessories were obviously new and selected with too much care and not much taste.”

The sentence is simple, an observation that shows an attention to details; but notice how the words are put in motion, given almost a feeling of drama, by the repeated use of “and.”

Newsweek said in its review that “Heinz writes with spare, Hemingway force.” The Saturday Review: “A novel as good as The Professional is in no way a mere derivative of ‘Fifty Grand’. It would have been written exactly as it was, and just as effectively, even if Hemingway’s story had never been published.”

Forty-three years ago reading The Professional, I began to see ways Bill Heinz stripped his prose of unnecessary words. I realized that said is the only verb you need to carry dialogue.

“What time is it?” Doc said, as we were finishing.

“One-twenty,” I said.

“That’s right,” Eddie said. “We better get to the studio.”

“You know why I’m doing this?” Doc said to me.

“No.”

“I’m a kindly old man. I feel sorry for that dame.”

“Ethel Morse?”

“Whatever her name is.”

The verb said nails it, gives it a beat. You don’t need answered, replied, suggested, averred, any of those. I learned also that you don’t need an adverb to explain how the line of dialogue is said. “Adverbs get in the way,” I now state authoritatively. They can destroy the rhythm of the sentence, distract, stop the flow of words cold. An adverb modifier is the author’s word, not the character’s; and if he is to remain invisible, his words must be kept out of the prose.

If there is even one adverb modifying the verb said in The Professional a copy editor slipped it in when Bill wasn’t looking.

You cannot imagine how important it was for me to learn these unwritten rules of writing. I had been writing fiction, Westerns, for only the past seven years. I knew I didn’t want to write in the classic style of the omniscient author, I didn’t have the voice for it, the language. Studying Hemingway I felt I was getting close to the style I wanted to develop. I began reading The Professional and there it was on every page.

In May 1959, I sent Bill a copy of one of my Westerns and told him I was working on another. In his reply he said, “I would like you to work at developing character through conversation—each person talks differently and so defines himself. You must be able to see and hear each character as he talks. You’ve got to try for a cleaner cleavage between the various manners of speech and of thought development.”

The review of The Professional in The New Yorker said:

This precise, poignant, and absolutely honest book examines, almost day by day, the month of training a middleweight prizefighter, Eddie Brown, undergoes at an upstate New York summer resort before his first crack at the world championship after nine years in the ring. It ends just after the fight, and the outcome, if devastating, is not in the least pitiless.

That’s what the book is about.

But to me it’s so much more. Over the years I’ve spoken endlessly of Hemingway being a major influence, failing to mention W. C. Heinz as the all-important link, the next step. It has taken a rereading of The Professional for me to see clearly where I came from.

Thanks, Bill.

Elmore Leonard

1

The subway is elevated there. There is something wrong about that, but there are long sections of the subway in the Bronx where it comes up out of the ground and runs along high above the street like the El. I suppose that some day they will put that under the ground, too, and that will be unfortunate because you can see a lot of New York from there, the way it is now.

I mean that often, as long as three or four days after a rain, you can still see puddles of water glistening on the flat, tarred roofs and reflecting the sky. On a windy day you can see the gray metal ventilators, some of them spinning and the others, with vanes like manes, snapping their heads in the gusts, sensitive and nervous the way you sometimes see a thoroughbred going to the post and trying to ease the bit with the boy standing on him and first hoping to soothe him and then swearing at him, if you could just hear it.

You can see the flower pots, too, on the fire escapes. Most of them have geraniums in them, but sometimes you will even see a rosebush, and always, a long time after they shouldn’t be there any longer, you’ll see the long, yellow leaves of Easter lilies, and the pink foil still around the pots.

“So why don’t you tell him?” a woman was saying.

There was an empty seat between us, and I was turned toward her so that I could look out of the window. She was sitting with another woman, and they were in their late thirties and their coats and their accessories were too obviously new and selected with too much care and not enough taste. I wanted to bet someone that they were going shopping and then to a movie.

“Tell him?” the other woman said. “Tell him what?”

When I got off at the station and carried my bag down the long flight of steps there was a cab parked under the structure and just back from the corner. The driver was reading a tabloid, folded and resting on the wheel in front of him. I opened the back door and lifted my bag in and got in and shut the door.

The driver was reading the Daily Mirror. He had it folded to that column called “Only Human” and written by a fellow named Sidney Fields, and I had time to see that at the top of the column there was a two-column cut of a cabbie, his elbow sticking out of the window of his cab and the cabbie smiling out over his elbow.

“Where to?” the driver said finally, putting the paper down on the seat beside him.

When I told him he started the motor and then he flipped the flag and shoved the shift in and made the right turn at the corner almost in one motion. I had to put my left hand out flat on the seat, but my bag fell over on the floor.

“Sorry,” the driver said.

“That’s all right,” I said.

“Guy’s got a story on a hackie in the Mirror,” he said.

“Oh?”

“He wants a story on hacking, I’ll give him one. I mean, I could give him plenty of stories.”

“I’ll bet,” I said.

It was a broad, black avenue. It was just 9:30 of a gray morning, with

the signs of early spring in the dampness of the litter in the gutters and in the mud tracked onto the oil-stained concrete aprons of the filling stations and of the garages where they do welding and auto-body repair. After a block or two the garages and the used-car lots gave way to old clapboard houses, all of them built high and square with porches on the front, here and there a porch enclosed with small panes of glass.

About a mile up the avenue we turned right and then made a left and another right. We started down a street of narrow duplex brick houses, each two houses pushed together and looking like one, except for the two concrete walks leading up to the separate entrances.

“You know the house?” the driver said.

“No, I don’t.”

The street itself was potholed, where the blacktop had given way, and now the holes held muddy water. Taking it slowly, the driver tried to skirt the holes, and then he settled for playing them as best he could.

“Got to be in the next block,” he said, “but these are good houses. They put them up about thirty years ago. They built good in them days. A guy owns one of these has got something, a nice home for himself and his family.”

The houses were not of really good brick, and some time ago the lime had weathered out of the mortar and left white stains. Between each pair of houses there was just room enough for a driveway, and in front of each house there was a small plot, about ten feet square. The plots afforded the only evidences of individuality. Some of them had low hedges around them and some were just grassed over with a shrub or two against the house. One of them had been concreted, so that it was of one piece with the sidewalk and the entrance walk and the driveway, except that the plot area had been painted light green.

“A guy’s doing all right, lives in one of these houses,” the driver said.

“But he should never come home with a load on,” I said. “He’d never find his own house.”

“You think you’re kiddin’?” the driver said. “One night I picked up a drunk at the subway lived on one of these blocks. He says he can’t think of his number, but he knows the house. It’s about three o’clock in the morning, and he tells me to stop at one of these places and he’s got no dough. He says his old lady will pay me. He goes up the steps and starts ringing the doorbell. A dame comes to the door and slams it in his face. Then he gets real mad. He starts kickin’ on the door. I get out and try to pull him off, and he rips two buttons off my shirt. Then the cops come. It ain’t the guy’s house. They find out he lives in the next block.

The Professional

The Professional